To complement Picasso’s major exhibition at Tate Britain ‘Picasso and Modern British Art’, Sin Fin Cinema presents Going Back to Reality: Portraying Pablo Picasso on the canvas in motion, a carefully selected body of films, ranging from documentary to experimental, from short film to video art.

This programme reveals the lesser known aspects of the Spanish artist’s life and highlights all those essential elements that have been distilled from his works influencing later generations of visual artists, such as the British David Hockey and Henry Moore.

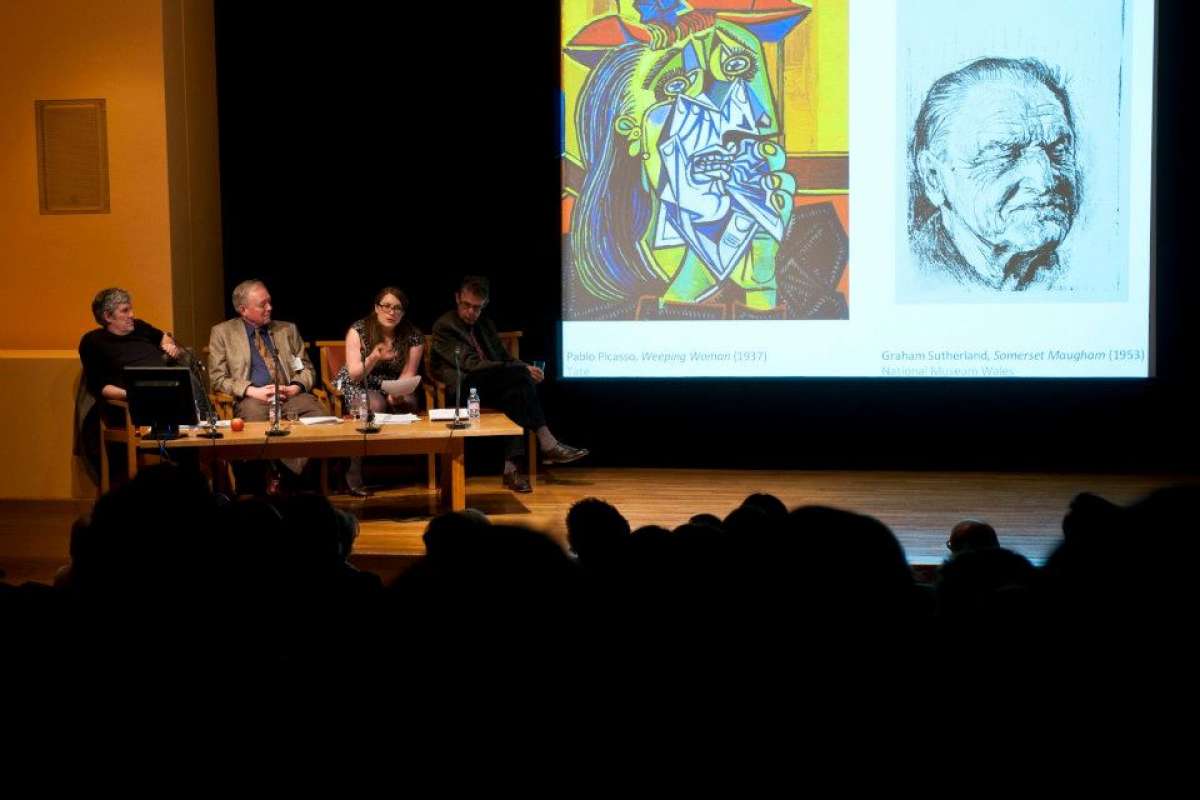

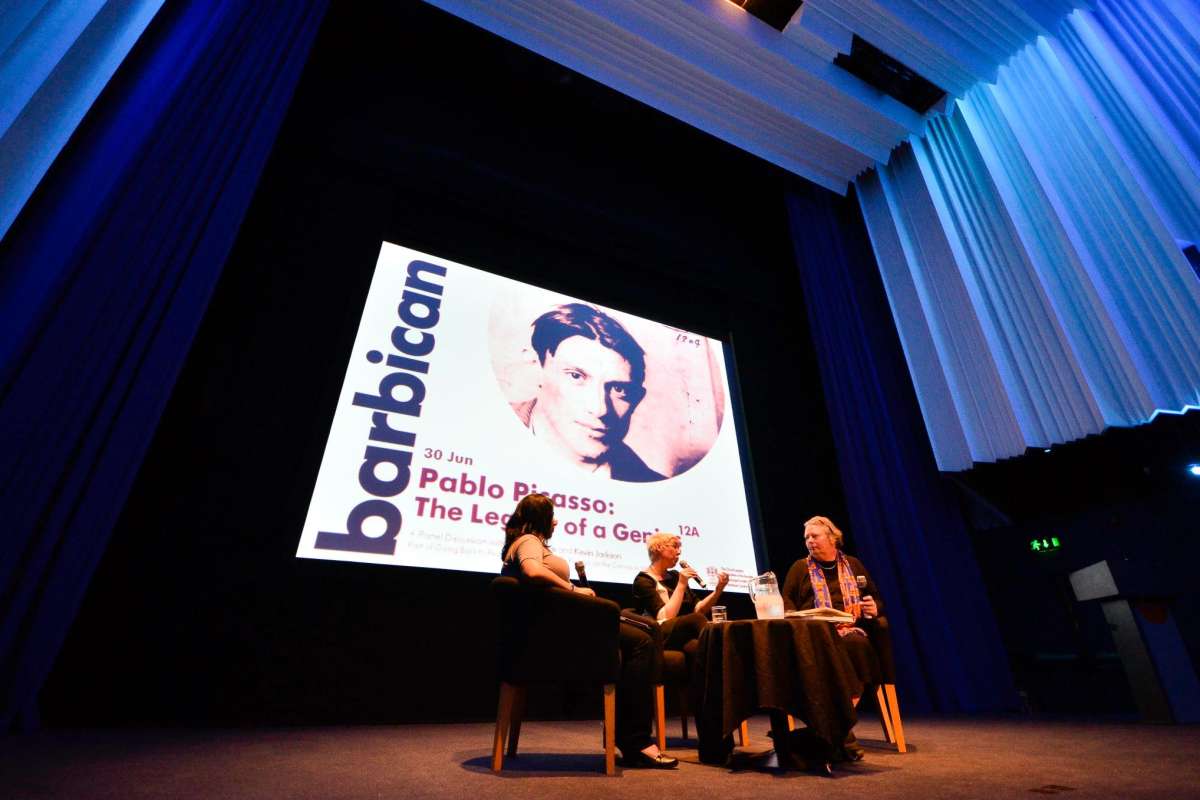

Going Back to Reality: Portraying Pablo Picasso on the canvas in motion launched on 2 March 2012 at Tate Britain, as part of the its celebrated event Late Tate. After, the programme spread over April, May and June, with Barbican, Instituto Cervantes and the French Institute hosting the screenings and special events.

The title refers to a 1981 interview between Melvyn Bragg and David Hockney. In it, Hockney offers a personal account of the development of modern art in the 20th century, and defends its frequent divergence from ‘photographic’ realism; he traces the beginning of the modern movement back to Van Gogh and Cezanne, and to the new interest in stylised Japanese art, which did not concentrate on verisimilitude. In that sense, Hockney maintains that the truly radical development was Cubism. This new technique of depicting reality, which Picasso and Braque developed in the summer of 1917, with its shifting points of view, selective focusing and reliance on knowledge of the subject, marked a breakdown in conventional representation. Using Picasso and Matisse as examples, he demonstrates the ability of modern styles to convey emotions and experiences more vividly than others. According to Hockney, Cubism was the only kind of painting faithful to reality after the advent of photography.

With this film season we are providing a unique opportunity to find out more about Picasso’s life and working process: his youth spent years living in Barcelona and Paris, the friends who surrounded him and the artists that inspired him.

It is undeniable that Guernica and its symbolism, which the artist never wanted to reveal, still continues to raise questions, speculations and investigations. Focusing on one of Picasso’s masterpieces, Going Back to Reality discloses some of the enigmas surrounding one of the world’s best known paintings. Further, with a special section devoted to British artists, this film season will also discover how cubism would find its way into the work of some of Britain’s major artists such as Duncan Grant, David Hockney and Ben Nicholson.

How Picasso became one of the most celebrated painters in the world and how he became viewed as a genius, are a few of the many questions that this film season will answer.

On April 26 1937, the small Basque town of Guernica was bombed without warning by the German aviation. Like millions all over the world, Pablo Picasso was shocked by the military atrocities, and translated his emotion and anger into a magnificent but terrifying canvas bearing the name of the martyred city.

The Guernica painting was commissioned by the Spanish Republican government to be displayed inside the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair Paris Exhibition, alongside two of the most significant works depicting and denouncing the horrors of the Spanish Civil War; Joan Miró’s The Reaper and Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain.

In a time when the Spanish Civil War was destroying Spain and the World War II was knocking on Europe’s doors, the international impact of the canvas, with a dimension of 349,3 cm × 776,6 cm, was absolutely enormous. Even today, this masterpiece continues to be embedded in the retina of our time.